By Denny Juge, CSO Phobio LLC

The Curious Case of the Universal IT Manager

There’s a peculiar phenomenon that occurs when you interview enough IT managers about device disposal. After about the fifteenth conversation, something strange happens. The individual voices begin to blur, and a singular character emerges from the collective—someone we’ll call Mike Ramirez.

Mike isn’t real, exactly. But then again, he’s more real than any actual person could be. He’s what designers call a persona—a fictional character built from the DNA of dozens of real IT managers across Dallas, Denver, Detroit, and everywhere in between. And his story reveals something profound about how we solve problems in the modern workplace.

Let me tell you about Mike’s 3 AM problem…

The Tipping Point of Technological Debt

Malcolm Gladwell once observed that small changes can make big differences. But what happens when small problems accumulate into overwhelming burdens?

Mike manages IT for roughly 500 employees. His team? Three people. Now, here’s where it gets interesting. In 1990, this ratio would have been impossible. But cloud computing, automated ticketing systems, and mobile device management created an illusion—that technology could scale infinitely without proportional human resources.

The illusion works beautifully until it doesn’t. And for Mike, the breaking point arrives in the form of 300 aging laptops.

Think about that number for a moment. Three hundred. It’s large enough to represent serious capital—his CFO calculated roughly $150,000 in potential recovery value. But it’s also small enough that hiring a dedicated disposal specialist seems absurd. Mike exists in what economists would call a “missing middle”—too big to ignore, too small to properly resource.

The Remote Work Paradox

Here’s where our story takes an unexpected turn. Forty-seven percent of Mike’s workforce is remote. In Phoenix, Portland, Pittsburgh—scattered like seeds in the wind. This should make things easier, shouldn’t it? After all, remote work is supposed to simplify operations.

But consider the paradox: every efficiency gained through remote work creates a corresponding complexity in physical asset management. When everyone worked in one building, Mike could walk the floors, collecting devices. Now? Those 300 laptops exist in 300 different locations, each one a unique logistical puzzle.

This isn’t just Mike’s problem. It’s a pattern we discovered across seventeen different companies, from professional services firms in Texas to manufacturing companies in Michigan. The distributed workforce didn’t eliminate the physical reality of technology—it atomized it.

The Psychology of Security Theater

Now, you might assume Mike’s primary concern is maximizing device value. His CFO certainly thinks so. But spend an hour in Mike’s shoes—or rather, in the composite shoes we’ve constructed from our interviews—and you discover something fascinating.

Mike’s deepest fear isn’t leaving money on the table. It’s the headline: “Local Company’s Data Breach Traced to Improperly-Wiped Laptops.”

There’s a concept in behavioral economics called “loss aversion”—we fear losses more than we value gains. But Mike experiences something beyond simple loss aversion. Call it “catastrophic imagination”—the vivid, almost cinematic ability to envision worst-case scenarios.

One IT manager in Denver told us, “I can see the breach happening. I can see the meeting where I’m fired. I can see my name in the industry publications.” Another in Dallas said, “Every old laptop is a ticking time bomb.”

This isn’t paranoia. It’s pattern recognition. Mike has read about every major data breach of the last decade. He knows that 60% of small companies go out of business within six months of a breach. The 300 laptops aren’t just assets—they’re 300 potential career-ending disasters.

The Gladwellian Moment of Revelation

Here’s where our story becomes genuinely interesting. When Phobio’s design team began studying this problem, they made a classic error. They focused on optimizing the wrong thing.

The initial assumption was elegant in its simplicity: IT managers want maximum value recovery with minimum effort. Build a better pricing algorithm. Streamline the logistics. Create a superior portal. It’s the kind of solution that would win awards at technology conferences.

But then something happened that changed everything. During interview number twenty-three, an IT manager in Austin said something that stopped the room: “I don’t want to think about this at all.”

Not “I want to think about this less.” Not “I want this to be easier.” He wanted complete cognitive absence.

This is what I call a “Gladwellian moment”—when a small observation reveals a fundamental truth everyone has missed. Mike doesn’t want a better device disposal process. He wants no process.

The Architecture of Invisible Solutions

Think about the most successful technologies of the last decade. What do they have in common? They disappear.

Uber didn’t create a better taxi dispatch system—it eliminated the concept of “calling a cab.” Amazon didn’t build better bookstores—it removed the store entirely. The pattern is clear: true innovation doesn’t optimize existing processes—it makes them vanish.

So Phobio’s design team faced a paradox worthy of a Zen koan: How do you design a process that doesn’t exist?

The answer came from an unexpected source—anthropological research into gift-giving economies. In many cultures, the most valuable gifts are those that remove obligations rather than create them. The gift of “not having to worry” is more precious than any physical object.

The Three-Touch Rule

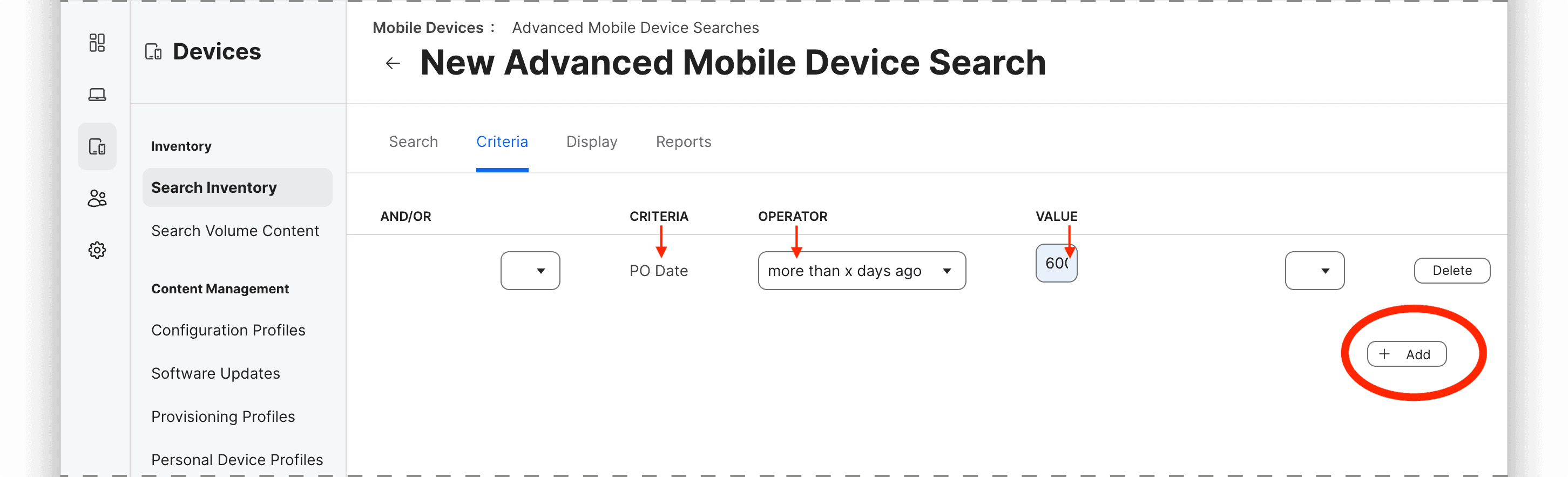

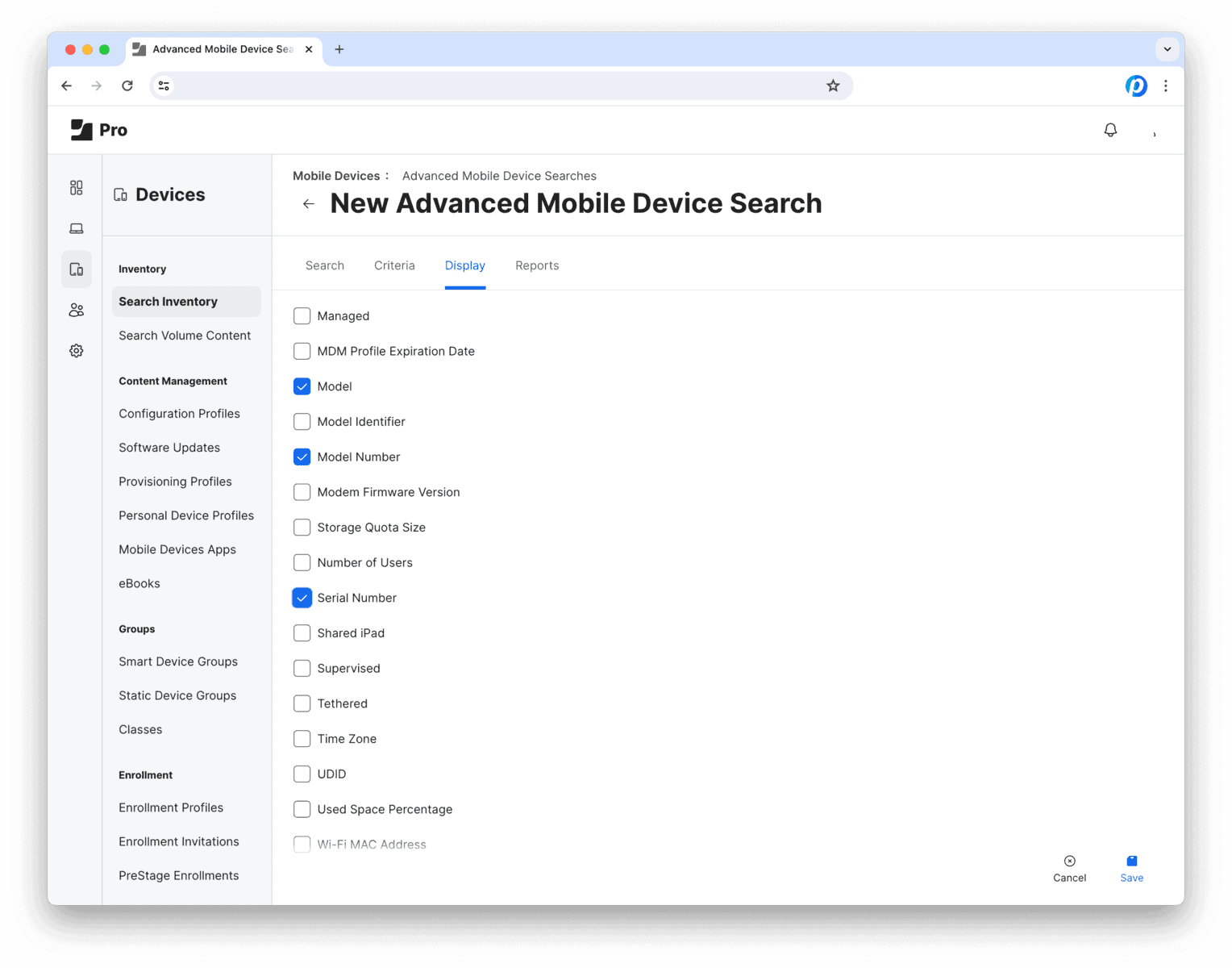

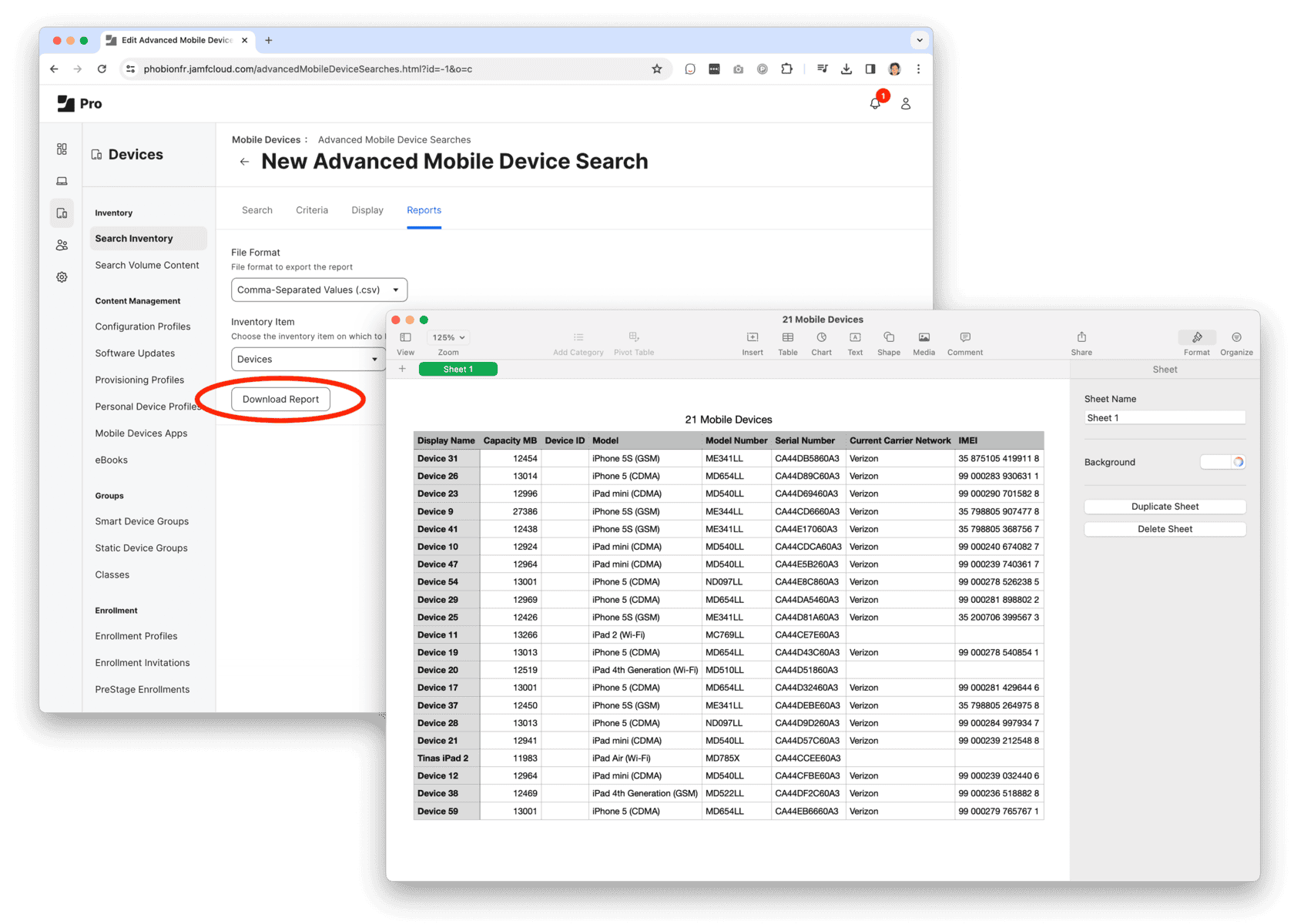

Here’s what emerged from months of iteration: the Three-Touch Rule. Mike should only have to interact with the disposal process three times:

- Touch One: The decision moment. A single email to leadership: “I’m initiating device recovery.”

- Touch Two: The packing moment. Boxes arrive pre-labeled. Mike’s team spends one afternoon placing laptops in boxes.

- Touch Three: The victory moment. A report showing recovered value and security compliance.

Everything else—coordination with remote employees, device assessment, data destruction, logistics across multiple states—happens in what designers call “the service backstage,” invisible to Mike.

But here’s the subtle genius: Mike can peek backstage whenever he wants. Full transparency is available but not required. It’s the difference between “can’t see” and “don’t have to look.”

The Network Effect of Trust

Remember, Mike isn’t one person—he’s a composite of many. And these many Mikes exist in a dense network of peer relationships. They attend the same conferences, read the same forums, share the same war stories over beers at IT meetups.

This network exhibits what network theorists call “high clustering”—IT managers tend to know other IT managers who know other IT managers. Information travels through this network with stunning velocity.

When one Mike in Dallas successfully disposes of 300 devices without drama, seventeen other Mikes hear about it within six weeks. But—and this is crucial—they don’t hear about it through marketing. They hear about it through what sociologists call “weak ties”—the casual conversations that carry the most trusted information.

The design insight? Don’t optimize for customer satisfaction. Optimize for story-telling. Make Mike the hero of a story he wants to tell.

The Behavioral Economics of Overwhelm

Let’s return to Mike’s 3 AM wake-up moment. Behavioral economists would recognize this as a classic case of “cognitive overload leading to decision paralysis.” Mike has what researchers call a “finite cognitive budget,” and every decision depletes it.

The 300 laptops represent what Barry Schwartz would call a “paradox of choice” multiplied by 300. Each device could be sold, recycled, donated, or stored. Each path has multiple vendors, each vendor has multiple options. The decision tree explodes exponentially.

But here’s what’s fascinating: Mike’s paralysis isn’t caused by the complexity of any single decision. It’s caused by the meta-decision—the decision about how to make decisions. This is why traditional solutions fail. They optimize individual decisions while ignoring the meta-cognitive burden.

Phobio’s approach was radically different: eliminate the decision tree entirely. One path. One partner. One outcome. The paradox of choice becomes the liberation of no choice.

The Story Arc of Modern Work

Every Mike we interviewed shared a common narrative arc. It goes like this:

- Act One: The young IT professional, eager to optimize everything, convinced technology can solve any problem.

- Act Two: The experienced manager, drowning in complexity, realizing that every solution creates new problems.

- Act Three: The seasoned leader, seeking simplicity, valuing partners who make problems disappear.

The 300 laptops arrive during Act Two, when Mike is most vulnerable to overwhelm. The traditional vendor approach—”We’ll help you optimize this process!”—speaks to Act One Mike, who no longer exists. Act Two Mike doesn’t want optimization. He wants liberation.

The Anthropology of Invisible Work

There’s a concept in organizational anthropology called “invisible work”—the crucial tasks that keep organizations running but never appear on performance reviews. For Mike, device disposal is the ultimate invisible work. Success means nothing happened. No breaches, no complaints, no drama. Just 300 laptops that quietly transform into budget dollars.

The cruel irony? Invisible work becomes visible only when it fails. Mike gets no credit for successful device disposal, but would get all the blame for a breach.

This creates what psychologists call an “approach-avoidance conflict”—Mike must act but is motivated to not act. It’s a paralysis born not of incompetence but of competence. Mike knows enough to know everything that could go wrong.

The Design Thinking Revolution

Here’s what makes this story larger than Mike, larger than IT, larger than device disposal: it’s a parable about modern work itself.

We live in an era of infinite complexity and finite human capacity. The solution isn’t to help people manage complexity better—it’s to absorb complexity on their behalf. The future belongs to what we might call “complexity absorbers”—services that take multifaceted problems and make them disappear.

Mike—our composite, fictional, yet utterly real Mike—doesn’t need better tools. He needs fewer problems. He doesn’t need optimization. He needs obliteration—the complete removal of cognitive burden.

The Epilogue That Writes Itself

Six months after implementing the Three-Touch Rule, something interesting happens in the network of Mikes. The conversation shifts. Device disposal disappears from the IT manager forums. Not because the problem was solved, but because it ceased to be a problem worth discussing.

At a conference in Dallas, a real IT manager (let’s call him Mike) says something revealing: “We processed 300 devices last quarter. I forgot about it until just now.”

That forgetting—that blessed, liberating forgetting—is the highest praise Mike can offer. In a world of infinite demands and finite attention, the greatest gift is the problem that solves itself.

And perhaps that’s the ultimate lesson of Mike’s story. In our age of overwhelming complexity, the most profound innovation isn’t doing something better—it’s making it so that something doesn’t need to be done at all.

The 300 laptops still exist. They still need to be processed. Value must be recovered, data must be destroyed, compliance must be maintained. But Mike doesn’t wake up at 3 AM anymore. The problem that once consumed his nights has become what it always should have been—someone else’s core competency, invisible to him.

That’s not just good design. That’s understanding the hidden architecture of modern work. And once you see it—really see it—you realize Mike’s story isn’t about IT management at all.

It’s about all of us, drowning in complexity, searching for partners who can make our problems disappear. Mike isn’t just a persona. He’s a mirror.

And in that mirror, we see ourselves at 3 AM, wondering how we got here, and more importantly, how we might escape.